NEWS & INSIGHTS | Opinion

Hydrogen and electrification ladders: A strategic view for the UK’s net zero transition

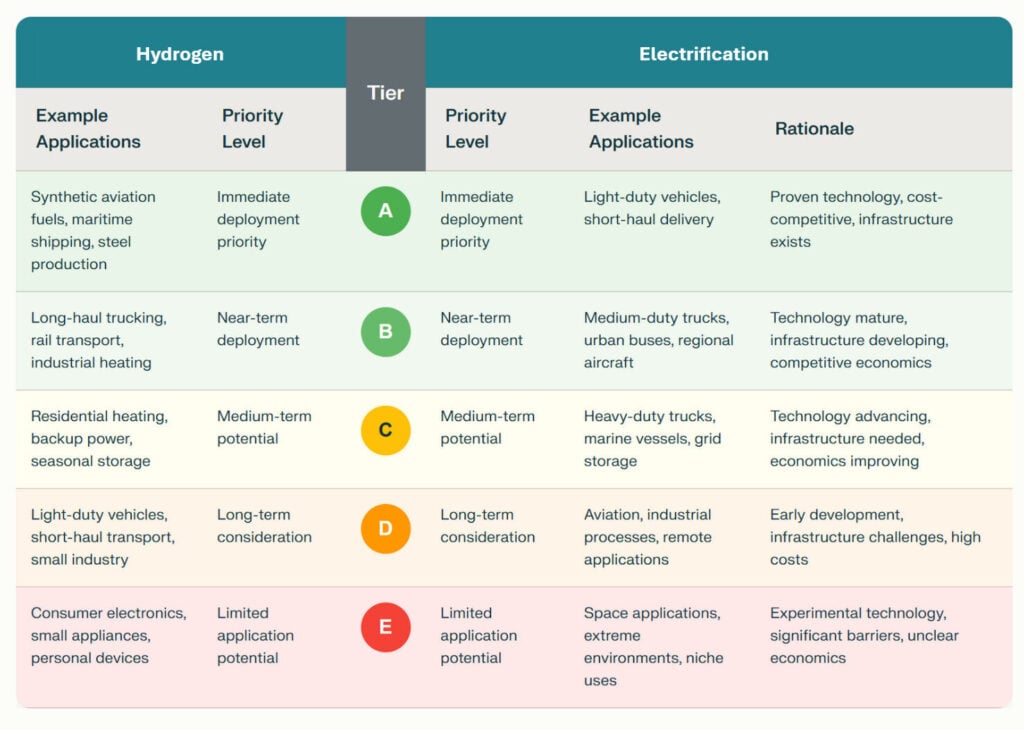

As the UK accelerates its journey toward net zero, the question of where to deploy hydrogen versus direct electrification is rapidly moving from theory to real-world investment and policy decisions. Globally, similar debates are shaping the energy transition strategies of leading economies. To navigate this landscape, it’s useful to visualise the options as two “ladders”—one for hydrogen, one for electrification—each ranking end uses by their suitability, scalability and impact.

Why ladders matter

The concept of the “Hydrogen Ladder,” popularised by Michael Liebreich, has become a touchstone for policymakers and industry leaders. It provides a clear, evidence-based hierarchy of where clean hydrogen is most likely to deliver value. While there is no single, universally adopted “Electrification Ladder,” the logic behind one is equally compelling and for the most part it is the inverse of the hydrogen ladder (with a few exceptions). What the two ladders tell us: electrify wherever possible and reserve hydrogen for the hardest-to-abate sectors.

To bring these ladders together, consider the following:

Hydrogen ladder: Prioritising the irreplaceable

In the UK and globally, hydrogen’s greatest impact will be in sectors where there are simply no viable alternatives. At the top of the ladder are applications such as chemical feedstocks (ammonia, methanol), fertiliser production and certain steelmaking processes. These are “no regrets” uses—hydrogen is essential and decarbonising them is non-negotiable.

The next rung includes long-duration grid balancing and some forms of heavy transport, notably shipping and synthetic aviation fuels. Here, hydrogen or its derivatives (like ammonia or e-fuels) offer strong potential, with the UK investing in pilot projects and infrastructure.

Lower down the ladder are uses where hydrogen is possible but less compelling—industrial heat, remote trains, and ferries—often competing with electrification. At the bottom are sectors where hydrogen is simply uncompetitive, such as passenger cars, metro trains and most building heating. The UK’s own hydrogen strategy reflects this, focusing on industrial clusters and heavy transport, while keeping options open for future developments.

Electrification ladder: Scaling what works

Electrification, by contrast, is the UK’s default decarbonisation tool for sectors where electrification technologies are already mature—such as displacing petrol vehicles with electric vehicles, or using solar and wind power to replace fossil fuel-based electricity generation—efficient and cost-effective. At the top of the electrification ladder are passenger vehicles, buses, trains, building heating (via heat pumps) and most household appliances.

The IEA’s global EV outlook 2025 highlights the key advances and trends in battery technology that’s driving the electrification of vehicles. Since 2020 EV ranges have increased from an average of <210 miles to 310-370 miles with some premium models boasting up to 500 miles range. These advances come thanks to advances in battery energy density.

The next tier includes light industry, local delivery trucksand short-haul aviation—applications where electrification is advancing, but technical or economic barriers remain.

For heavy industry, long-haul transport and aviation, direct electrification is often impractical, pushing these sectors further down the ladder and opening the door for hydrogen or other solutions.

UK and global trends: Convergence and leadership

The UK’s approach—electrify wherever possible, deploy hydrogen where necessary—mirrors strategies in the EU, US and Japan. The UK is undergoing a major transformation of its energy system, aiming to deliver a new era of clean electricity by 2030. Under the government’s Clean Power 2030 Action Plan, at least 95% of Great Britain’s electricity is set to come from low-carbon, clean sources by the end of the decade, with the remaining 5% provided by gas generation only when absolutely necessary. This ambitious target is a crucial step toward fully decarbonising electricity generation by 2035 and achieving the UK’s broader net zero goals. Coupled with the government’s commitment to 10GW of low-carbon hydrogen by 2030, positions the UK as a global leader in both technologies.

The bottom line: Clarity for action

The hydrogen and electrification ladders are not static and need to be revisited as new innovations and breakthroughs occur. They are a valuable tool that offer a strategic framework for making smart, targeted investments. For policymakers, the message is simple:

- Electrify everything you can

- Use hydrogen only where you must

For business leaders and investors, this clarity helps focus resources on the sectors and technologies with the greatest potential for impact and growth. The biggest risk now is not a lack of options, it’s misalignment. Backing the wrong solution in the wrong sector could lock in emissions, waste capital and delay progress. As the UK and global economies move from ambition to execution, the challenge is no longer whether to act—but how, where and when. Climbing the right ladder—at the right time—will be the key to success.

Subscribe for the latest updates